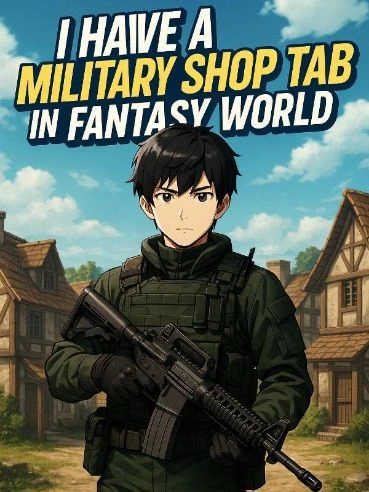

Chapter 174: The Boss Fight Part 2

Words : 1632

Updated : Oct 12th, 2025

Chapter 174 of "I Have a Military Shop Tab in Fantasy World" opens with: The tide hit and broke. Lyra’s first volley was merciless—three arrows in a fan at kissing... See what unfolds next!

The tide hit and broke.

Lyra’s first volley was merciless—three arrows in a fan at kissing distance. The front rank of hatchlings crumpled under the impacts, limbs knotting, bodies flipping. Inigo met the next line with short, economical bursts; the M4 spoke in staccato, each report a clean punch through chitin. Smoke bit his eyes; heat licked his cheek. One hatchling got close enough to smell him—chemical, oil, steel—and he stamped it flat, boot crunching through head plates.

"Right flank!" Lyra warned.

He pivoted, dashed—a blue smear through heat shimmer—and skidded low under a leaping pair, shooting up into their bellies. Black ichor rained. He came up running and slid behind a boulder that was rapidly turning into a boulder-shaped oven.

The Broodmother forced herself forward two dragging lengths, the floor stuttering under her, legs scraping for purchase on a melting, treacherous web of her own making. Blind eyes found nothing; the ruined eye wells bled slow and thick. She oriented by heat and vibration now—and both told her the same thing: kill the bright, loud pain in the room.

"Inigo, above you!" Lyra’s voice cut clean through the noise.

He looked up. A hatchling bigger than the rest—armored like a captain spider—dropped from an upper strand, angle straight for his face. He went backward in a no-step lean, felt the air of its fangs on his nose, and fired from the hip up its throat. The thing shook, thumped onto his boots, jerked twice, and stilled.

"Thanks," he said, breathless.

"Don’t die," she shot back.

"Working on it."

The room’s geometry changed again. A load-bearing sheet of silk overhead flashed to vapor; a tongue of ceiling stone broke loose and fell like a guillotine. The Broodmother staggered, took the hit across her back plates; cracks spidered—fittingly—across the carapace. She answered with a spit fan—wild, wide, a tantrum cut loose. Acid hissed everywhere. A droplet caught Lyra’s bracer and smoked; she ripped the leather off with her teeth and flung it.

"Eyes on the seam," she said, pointing with arrow-tip to the head-neck gap now studded with her shaft. "It’s widening."

"Good," Inigo said. "We’ll make it a door."

He scanned fast. His last incendiary was gone. He had two flashbangs left, but the queen was beyond blind; light and sound were just pain now, not impairment. The rope he’d used was slag. The torches they’d brought burned low on the floor, more grease than flame. But the oil the guild had cached...

"In the shack," he said. "Barrels."

Lyra understood mid-sentence. "We don’t have time to fetch."

"Don’t need to." He jerked his chin toward the secondary tunnel barely visible through the heat haze—where the miners had dragged supply casks before they died. Against the wall, half-swallowed in silk, he saw them—four squat shapes with iron bungs.

He dashed.

The world stuttered as the enchantment grabbed hard. He ricocheted off a tilt of broken floor, skated through a curtain of heat like a ghost through a veil, and arrived chest-first into a snarl of half-melted silk. He tore at it with gloved hands, grabbed the nearest barrel, and heaved. It stuck; he swore; he heaved again, muscles shuddering.

A hatchling hit his back. Claws skittered on his vest; he slammed its head into the wall and smashed his elbow into its face twice, then shoved the barrel free and rolled it along the floor. It wobbled, then caught momentum, heading toward the Broodmother like a beer keg of doom.

"Lyra!" he shouted.

She saw it, got the line instantly. She drew an arrow and kissed it with the torch’s last ember, the fletching lighting like a dry leaf. The arrow tip burned, a comet bead. She fired low; the shot rang off the barrel’s iron bung, sparks and flame spitting, but the seal didn’t crack.

"Again!" Inigo yelled, shoving a second barrel free. He launched it with a kick.

The queen began to move back—instinct for depth, for nest, for tight confines—but the melted silk made every movement a slide. She turned the wrong way once, hitting a wall, and a leg got stuck in a gummy rope. The second barrel bumped the first; both bumped her abdomen. She felt heat; she spat—missed; she screamed—found nothing.

Lyra’s second arrow hit the bung square. The plug popped. A gout of oil splashed over the abdomen, viscous, shining, running into seams and spinneret wreckage.

"Light," Inigo said.

Lyra didn’t answer. She simply snagged her torch off the ground, spun it to feed oxygen, and snapped her arm—an underhand throw that would have shamed any juggler. The torch bounced off a rear plate, then slithered down into the oil wash.

Fire bloomed like a flower.

The front rank of hatchlings panicked as the sudden heat wave rolled over them; some fled, some stuck, some turned on reflex to the brightest thing—Lyra—and died in a triple volley for their trouble. Inigo wove in front of those who slipped past, a blur, a hand, a muzzle, a kick, a burst. He fired until the bolt locked back on an empty mag and the click-click told him cold truth.

"Out," he said, voice flat.

Lyra fired two more, then murmured, "Four arrows left."

"Make them worth songs."

"I always do."

The Broodmother screamed and rolled, trying to bar-smother the fire on her abdomen, which made it worse—oil spread, flame spread, silk behind her caught, and suddenly the entire back third of the queen was a torch. She spun blindly, legs threshing, walls cracking.

The seam at her neck yawned.

"Now," Inigo said, and there was nothing light in him now.

He went low and fast and hard, a blue streak that became a man at the last step. He leaped—not as high as before, not as showy. Just high enough to catch the back lip of her head plate. His fingers found a purchase, burned; he ignored it. He used all the fire, smoke, rage, and weight in the room like a lever and wrenched.

The arrow Lyra had planted at the seam snapped. The seam opened more.

"Lyra!"

She didn’t hesitate. She ran three steps and jumped to a half-collapsed stone rib, boots skidding. She put her last heavy arrow on the string. She drew until her shoulders shook. She sighted the tangled junction—open, ugly—and let go.

The arrow flew, kissed smoke, and vanished into meat.

The Broodmother convulsed so hard the whole cave flinched. Inigo lost his grip, slid down her scorched plate, hit the ground on his shoulder, rolled, came up and did the stupidest thing he’d done all day: he tackled the queen.

He went for the mandibles. He put both hands on one and shoved it aside. She bit down. Jagged keratin punched through the sleeve of his jacket into his forearm. Pain lightninged to his brain; he screamed but kept pushing. He could feel the hinge beneath the flesh, feel where it wanted to move and where it didn’t.

"Break," he snarled through teeth.

Lyra, breath tearing, dug in again. She saw it—Inigo, tiny against that thing, hands on a nightmare’s mouth like a fool and a hero. She didn’t have arrows. She had herself. She leaped down, rolled under a flailing leg, came up beside the mandible and slammed her bow like a prybar into the other hinge. She braced feet and pushed.

Something gave.

The mandible snapped outward with a wet crack.

The queen screamed all the sound she had left.

Inigo ripped his bleeding arm free, planted a knee on her mouth, and with his other hand drew his sidearm—a compact handgun he rarely used. He shoved the barrel into the gaping seam Lyra had opened between plates.

He looked into her ruined eyes. "No more."

He fired three times.

The Broodmother went still.

Silence rolled in like surf after a storm—hiss of burning silk, smash of fallen stones settling, the tick-tick of cooling chitin. Lyra staggered back, face ash-streaked, hair matted with grime, bow clutched like a lifeline.

Inigo stood very still for a count of five, then stepped off the queen’s head and let himself breathe again. The adrenaline backwash hit; his knees thought about failing and decided not to. His forearm bled clean, the holes already weeping poison-black at the edges.

Lyra saw it and was moving before he was. "Sit," she commanded, voice not brooking argument.

He did.

She tore her satchel open and yanked free a squat clay vial. "Antivenin?" he asked, trying to sound wry and landing at tired.

"Guild standard for arachnids," she said, breaking the wax and pulling the cork with her teeth. "You’re lucky I nagged you to carry it."

"I’m lucky you nag me to do anything."

She poured the thin liquid over the punctures; it stung like betrayal. He hissed and bit his lip. She wrapped his forearm in a clean linen roll, tight enough to stop bleeding, loose enough not to cut circulation.

"Any tingling?" she asked.

"Yeah," he said. "But that might just be because I fought a building-sized spider with my hands."

Her smile was cracked and perfect. "Idiot."

"Manager," he corrected.

Smoke thickened. Fire burned along ceiling tangles but had begun to burn itself out where silk was gone. The room smelled like roasted horror. He put his palm on the queen’s carapace—a soldier’s habit, a hunter’s respect—just for a second, then withdrew it.

"Proof," Lyra said, already moving practical. "The Guild will want evidence. Fangs?"

"Fangs," he agreed. They worked together—she braced, he cut with his field knife at the gum line, twisting. The fang was a curved dagger in its own right. They bagged two, then took a spinneret cluster, a plate shard that bore distinctive markings, and a vial of venom that they carefully milked into a stoppered glass.

Comments (0)